Getting Out of The Way

Reese Madigan on Coming Back to Next Act Theatre

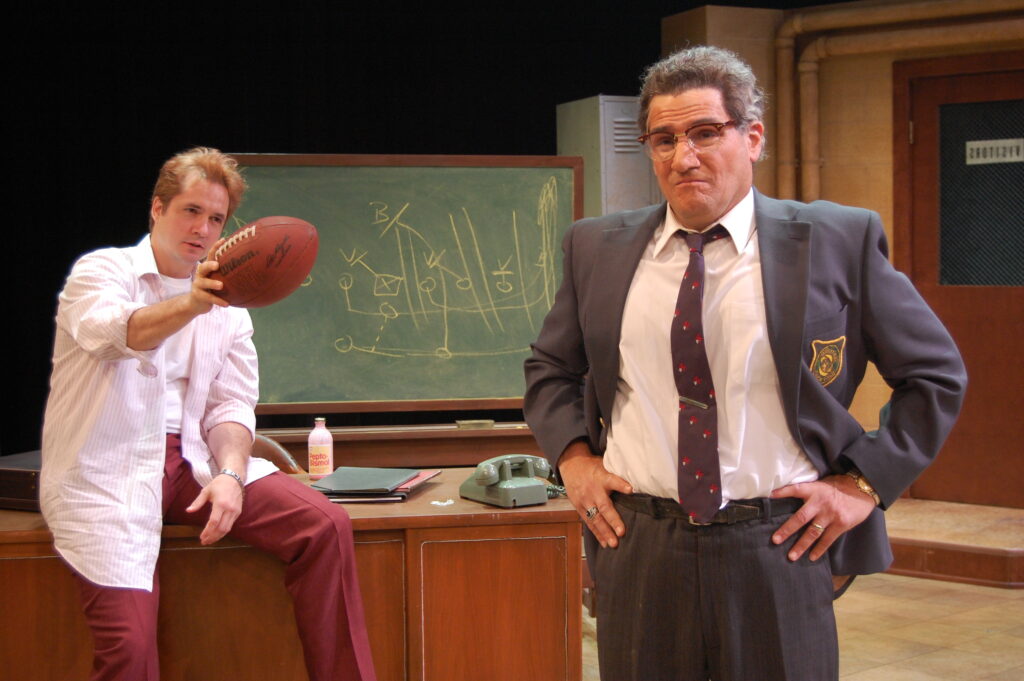

Actor Reese Madigan returns to Next Act Theatre in the role of The Son in THE TREASURER by Max Posner, running April 24 – May 19, 2024. He was previously seen in our 2017 production of SILENT SKY and our 2008 production of LOMBARDI. We caught up with him to learn more about his return to Next Act and what he’s looking forward to with this play.

Tell us a little about your history with Next Act Theatre.

If I really think about it, it spans a pretty significant period of time: from [Eric Simonson’s play] LOMBARDI. I got to reprise the role of Paul Hornung at the [Milwaukee] Rep when they did the Midwest/post-Broadway premiere. The Off-Broadway Theatre was a great little intimate space, and the fact that they kind of expanded it [with the current space] while keeping that wonderful intimacy—minus the pillar that we had to work around—was kind of great.

What I liked so much about Next Act really was… certainly the audiences, but I have to say that David Cecsarini was central to my experience. I think that probably goes for everybody who’s worked there. The fact that he did everything and completely led by example. In the case of LOMBARDI, he was Lombardi, and he was a brilliant Lombardi. But I have this one memory: there we were, he’s in LOMBARDI, he’s got the nose, we’re a full house, and a lightbulb needed to get changed in the men’s room – and David was going down the hall to make sure that happened. And he could have passed it off, and he probably should have passed it off, but I was so taken with the kind of artist that he is. The fact that he is not only a good actor, but a good director—and a really good director and a really good actor—and a really good sound designer, and kind of just did everything. A real man of the theatre who just… it was happening because David was there.

He was the stone in the entire stone soup, and the soup was really, really wonderful in the case of LOMBARDI. It was a strange show, I mean, not at all like the Broadway production. We had Mark Ulrich as Saint Ignatius Loyola playing sheepshead with “Red” Blaik, who ran West Point, and John F. Kennedy at one point, and Hornung, and it was really kind of this very strange fever dream of a play, but the size of it and the intimacy of it really made for such a rich story. It was a terrific experience because everyone was sort of fishing after the same thing, and the audience was as committed to showing up and being there as everyone in the room. David hired people who really wanted to be there and really wanted to dig and delve and figure this strange little piece out.

Cut to the new space, which is gorgeous. I had the pleasure of playing there this fall in WITCH for Renaissance [Theaterworks]. There’s such a good energy in the building! But obviously, SILENT SKY was a few years prior, and that was so cool to take this new-ish theatre, at the time, on a test drive. It’s a great space to be in. It’s so intimate. You feel like you’re being hugged by the audience, and it allows for a real intimacy in performance that sometimes you can’t get if you’re in a larger space. And I got to work with Deborah Staples, who is an old friend of mine and one of my favorite actors in the world, and with Kelly [Doherty] and with Carrie [Hitchcock] and Karen [Estrada], and that was a fantastic experience. I was sort of the one male in that show, in that room, and that was really a great group of women to be a part of and to just sort of keep handing the “hot potato” off to. They were all so wonderful and I was just there to facilitate the story and help tell this great story of this brilliant, groundbreaking astronomer. Again, it was a similar kind of thing: the audience arrived ready to enjoy the show.

That’s been my experience with both productions, and I think [that’s] because such love, and such craftsmanship and such care has gone into the stewardship of this theatre. I couldn’t be more elated that Cody is now at the helm. We’ve had occasion to get together and talk a little bit and I just get such a good vibe from him. Somebody who also was central to theatre in Chicago and now he’s central to Next Act, and I think you need that kind of committed artist to be running it and making it run on all cylinders, and I think it’s in really, really good hands. I couldn’t be happier that it’s been handed off to a person with such good taste, and such a big heart and such a desire to make stuff. Cody’s enthusiasm is infectious, and I am absolutely thrilled to be a part of this production.

How do the directness of this play and the intimacy of Next Act’s space work together?

First of all, it’s as good a piece of writing as I’ve read in years and years and years. I think this is a brilliant play. For me, the most exciting moment in the theatre is when the lights go down, and we’re alone in the dark together, and then the lights come back up and we have them for a little bit of time. We have them until we lose them.

What Max Posner has written, I think it’s a great opportunity to begin the show having the actor say, “hey, I’m here with you. We’re breathing the same air. There’s no line between me and you.” I mean, I might as well be sitting in a seat next to somebody and just get up and start this conversation. It’s a rare opportunity to say, “okay, this is where we are now. We’re in the here and now. Here’s a little bit about me. And P.S., here’s a little bit more about me and this strange situation that I find myself in. I’m not really sure where we’re going, but we’re in this together.” That’s really the overarching thing that I want to be able to achieve in those early moments: there is no line between actor and audience. We are in the same space. Not to lose that, not to turn it into this thing which is distant, because it’s such an intimate play.

It deals with things that, if we haven’t dealt with them, we’re all going to have to deal with them: mortality, and responsibility, and fear, and love, and, to a degree, faith, regret, remorse and, beneath all of it, it’s written with such a light touch that it’s about love. This is a play about love, and how do we love each other? And how do we reconcile difficult emotions? And how do we go through life with each other, making great mistakes and trying to mend them? And keeping going forward.

Because even though this character of The Son purports to have these deep resentments, and he says, “I can’t talk to her for more than two, three minutes,” it’s very confidential. It feels like this guy has your elbow. He’s kind of saying, “listen, between us, she makes me absolutely crazy. That’s just the way it is. But let me tell you about my family, about my son.” He gets to be quite candid very immediately. One of the tricks of it is, he says, “talking in front of people is my idea of…” He purports not to want to talk in front of people, but he begins the play. That’s the interesting conundrum: he says, “listen, I’m not good at talking in front of people, I don’t like to talk in front of people,” and yet he’s written with this facile, disarming kind of banter that draws people in. That’s really what I’m hoping to do is to be able to say, “come on in. Let me tell you about myself and maybe you can tell me about yourself.” Because certainly, everybody’s going to have that experience in life.

The way the dialogue is written, it is so conversational, it is so much like people talking, he has so many fits and starts, he has so many parentheticals, he has so many digressions. It has been a bear, but a real joy, to learn these big pieces that don’t really involve anybody else but me and the audience. To be able to find the character’s rhythms just by trying to memorize the words has been a real treat. In some ways, the playwright has given you the heartbeat of this guy in the first eight to ten minutes. I’m obviously very passionate about it, and I think that it’s the most important part of the play, and I feel like we have an enormous opportunity ahead of us to be able to start the play like that. If I don’t fuck it up. So, I’m really excited to not fuck it up.

It’s interesting how the characters are very indirect with one another, but The Son is very direct with the audience.

I lost my mom in 2022, and she had a very fast-descending, mysterious case of dementia. She went from being very independent to being incapacitated within weeks. She lost the ability to speak after a while, not very long after that. My mother was a National Merit Scholar and a very verbal, brilliant person.

Especially in the last year of her life, I spent a lot of time with her. She was ill during the pandemic, so I had a lot of time, which was a great gift. I would talk to her for hours, and she often wouldn’t have anything to say, but I could be very, very candid with her and open up in ways that I never was able to in my life because we were down to it. The handwriting was on the wall. When you have an audience who’s listening to you and is not talking back, there’s a way that you can unburden yourself and be more candid than you expected you would be at the beginning of the conversation. I found myself telling her things—thank God—that I probably would not have been able to had she been able to be more conversational. I knew that she was in there even though she had a terrible aphasia. That made for a one-sided conversation but a real connection because she was present.

Even though the audience isn’t the mom and doesn’t have that same relationship, it’s a real luxury to be able to speak for a long time, and I think that’s a luxury we have with this play, at least in the beginning, is that it’s a way to just come into something gently. You find yourself in the middle of it without realizing that you’re there. I think that’s the opportunity that we have – that easy, conversational way into the middle of something which is impossible.

It’s performed very realistically, the way that it’s written. Even though it’s not a conventional, one-set, realistic set, these are very realistic scenes. Even if they’re in snapshot or in this fever dream, they happen realistically, and I think that the way that I speak to the audience is going to train their ears to pick up on that very realistic way of actors speaking to each other as well.

How do you approach bringing your real-world experience into the play? Or do you?

We have no other tools in this strange art form. We are the instrument, we are the violin. I know that it’s a little bit of a cliché, in terms of “my instrument,” or “I just have my instrument,” but it is the truth. You don’t have any other media to use other than what makes you human, which is how you perceive the world, what you see, hear and feel, and then how you are able to communicate that visually, and auditorily and, I guess if you can touch the audience, sometimes kinesthetically. But you don’t have anything other than yourself. It’s really unadorned.

I think this play is stripped of a lot of artifice and adornment. It asks me, and I think everybody in it, to really bring their heart to… again, the heart is a metaphor, but it’s the most important tool I have, I think, in my work. [Sigh] This play asks you to be very, very open. It asks you to be as loving as you can be. It asks to be as imperfect as you can be. It asks you to be cruel. It asks you to beg forgiveness.

I don’t really get afraid of indulgence or emotion for the sake of emotion. I would rather see too much of that on stage than too little. But that’s my own personal taste. However, here’s what I think: the highest level I can have as a performer, when I’m operating at my best—and it doesn’t happen but rarely, a few times during a performance if things are going well, hopefully at least once during a performance, and you’ll have nights when you’re soaring—but I think that the ideal is to get the hell out of the way. You do all of this work to be a vessel for something which is larger than you.

The only way you can do that is to practice being open and being vulnerable and showing up with all of you to rehearsal. If you’re scared on the day telling the truth, if you’re scared about the work, if you’re insecure, state what it is, and then keep going. That’s the way I try to work. I can only start with where I am. I can only start from zero.

Yeah, it’s true that I lost my mom to dementia, but my mom was also very different than Ida, and our relationship was different. But here’s what I was: I was a son and she was a mother. And that’s a universal thing. And if I can get out of the way…

It’s so much easier said than done. That’s what all the work is for. That’s what all the training is for, the drama school, the technique that you either have, or you don’t or who cares. We all have our own ways of working. It’s the Prayer of Michelangelo: “Lord, please free me from myself so that I may please you.” That, to me, is my creed at core. I read it in an Al Pacino biography, like, 30 years ago. “Lord, please free me from myself so that I may please you.” And it’s as close to my heart and the way I work as I can be. Because all that work goes into creating this thing, and then you take a breath and try and get out of the way.

And sometimes, you have that experience of being taken by the seat of the pants flown up to the stars. If it’s a good play. O’Neill will do that to you every time, Tennessee Williams will do that, Shakespeare will do that, great playwrights will do that, and I think that this is a great play. I’m very much looking forward to doing the work, and then hopefully just trying to be The Son. To be that archetype. Because we’re all sons and daughters, and parents and children, and in that way, this play will remind us what it means to be human. If we get it right. In a very profound way, I think.

You also write plays. How does being a playwright inform how you act?

If anybody’s ever sat their butt in a chair and tried to write a play, it at once gives you an enormous respect for how hard it is to be a playwright, and at the same time gives you a little bit of impatience if you feel like something has not been thought through. And I don’t say that with ego, but I say it as: I’ve come to write plays through the backdoor, as a lot of us have. Shakespeare included. And I don’t put myself in his category. [Laughs] But I think being an actor, if you’re trying to write a play, is enormously useful.

And especially in Milwaukee, the great benefit I’ve had is to have worked with so many great actors and directors and have gotten to know some of them. Like Laura [Gordon] – being directed by her and being in DEATH OF A SALESMAN with her are two completely different experiences, but the heart is the same, and the shorthand gets a little bit easier, and there’s a level of trust which you cannot buy going in cold to a room. I’ve learned so much just about acting: about moments and how they’re constructed, how great actors come and figure their way through, get out of the way of great work and put their shoulder to plays that need to have their shoulder put to them.

You get an ear for rhythms. The litmus test is, “can I do this? Can I ask my friends to do this?” And if the answer is “no,” you have to rewrite it. Could I ask an actor to do this? Does it pass the smell test? As much as I want to fill in this little piece that I need to put in to finish the play, it has to be playable, and it has to be something that an actor can dig their teeth into.

My only qualities that work as a writer are what I’ve learned as an actor in the theatre about language, about rhythm, about timing. About how rhythms change over the course of a play, about how you need to change rhythms all the time to keep an audience engaged. The rate of change has to be very quick. But, you know, also, especially with the last play that I wrote, there are some amazing actors in Milwaukee, and I had them reading my play. You can’t buy that, to be able to write a play knowing how it would come out of somebody’s mouth and then have the experience of it come out of their mouth in a way that’s even better than you imagined. It was the best thing in the world.

Acting is a humbling process. Writing is a humbling process. I think the lessons I’ve learned about trying to be selfless, and getting out of the way of the story, and what’s essential here, and what’s not, and what’s (if you will) indulgent, and what’s not, and what building blocks do we need to move this story forward, and to keep it changing and to keep people engaged? All of that stuff I learned as an actor.

What keeps you coming back to Milwaukee?

It’s made by the artists who somehow find themselves in Milwaukee. From all over the place. What brought me to Milwaukee was, in 1999, I was cast in a production of CAT ON A HAT TIN ROOF. It was a dream role for me, Tennessee Williams is my favorite playwright bar none. I was playing a former, kind of broken-down athlete, and so every morning, I was trying to get myself into that frame of mind, so I was running with a football. I did not play football growing up, but I bought myself a football, and that was my totem, and I was running with it in Brooklyn.

I got to Milwaukee, and it was my first day, and I was running with it, and I had just quit smoking, so I was doing my best. I was out on the Oak Leaf Trail, my first morning in Milwaukee, it was September 30. I will never forget this. I was so stunned by the lake, and then I went running, and I was like, “there is something familiar about this place, and I don’t know what it is.” To this day, it feels like home to me, and I don’t know why.

And I’ve heard that from other people who’ve come from other places as well. There’s something about it that feels like home. And I’ve felt that kinship in the rehearsal rooms as well. I think what makes Milwaukee “Milwaukee” is the people – whether they’re the fine artists who have been born in Milwaukee, or the many artists who were born all over the place who have chosen to live here. Because it’s so special. Because of the people. You can’t buy that. There’s a familiarity that everybody has. You get to work with people you know. You get to be in rehearsal rooms with people you know. You get to grow up in many ways.

I think we’re all fishing after the same thing. Everybody’s heart is in the right place. And I’ve never been around such a concentration of talent. I’ve been fortunate enough to work in a lot of different cities, and I think Milwaukee is the most special. It’s great artists choosing to make it their home. I can’t account for why they’ve all done it, but I know that great art is created on a regular basis in Milwaukee, and I think that’s why they stay. And thank God.

What do you hope the audience takes away from this play?

“That’s me. That’s my mom. I recognize that. I recognize myself. I recognize my family.” I want them to see themselves in it. And perhaps gain a measure of compassion and forgiveness in themselves of what it means to be human.

Because I think that’s what this play is about. This play is about what it means to be human. And what it means to be human is to be flawed. To perhaps have a little compassion for themselves, because life is hard. And it’s also extraordinarily beautiful. But it takes endurance to run through the spectrum of all that.

Anything else you’d like to add?

My enormous gratitude, to not only be a part of this play and Next Act once more, but to be continually welcomed as a part of the rehearsal rooms and performance spaces in Milwaukee. It is the most special place in the world to me. It’s a privilege to work there.

THE TREASURER runs April 24 – May 19, 2024 at Next Act Theatre. For tickets, click here or call (414) 278-0765.