Behind the Curtain

“HAPPINESS” in Conversation with Mary MacDonald Kerr, Cassandra Bissell and Mickle Maher

THERE IS A HAPPINESS THAT MORNING IS by Mickle Maher is hard to describe in one sentence – or a whole paragraph. In order to prepare for Next Act’s production of this play, we put Mickle in contact with director Mary MacDonald Kerr and actor Cassandra Bissell, who plays Ellen.

Cassandra Bissell: First off, I just have to tell you that I’ve always got one foot out the door with regards to continuing theatre, and last winter saw me in a particularly dim and hopeless place. When David Cecsarini sent me THERE IS A HAPPINESS THAT MORNING IS, it felt like the Universe saying “Wait! Don’t go yet! Try this!” So, for whatever it’s worth, you ought to know that this play has been a kind of beacon on my horizon. I’m a little terrified of it, but in the best possible way.

Mary MacDonald Kerr: When/why did you become a William Blake fan? Assuming that you are, of course…

Mickle Maher: When I was a student at the University of Michigan, early ‘80s, Allen Ginsberg came and read/sang at Rackham Hall in its beautiful old Art Deco auditorium, which looked like this:

He did his own poems, of course, but the finale was Blake’s “The Nurse’s Song,” which he sang, accompanying himself on harmonium. The last line of the poem/song is “And all the hills echo-ed,” which he encouraged us to sing along to, and this being groovy Ann Arbor, the whole audience did, repeating that line over and over for forever. And it was kind of glorious. I think I’m still there, howling away.

CB: Was he the seed of inspiration for the piece, or did it start someplace else and he provided the sort of “vessel” by which to tell the tale?

MM: I knew I wanted to write about sex and love (very much so – I’d just come off a play about politics and murder and the very un-sexy George W. Bush and John Kerry), and I knew it was going to be in a dual lecture format, but the original subjects for the two lectures were MACBETH and mummification(!) It was a classic “Oh, duh!” moment when I realized Blake would be far better suited to the themes I was getting into. The story [included in the play] of him being found with his wife sitting naked in their garden reading Milton is probably fiction, but it feels true, and things that feel true are usually the cover pages for things essentially and consequentially true, and so make for good subject matter.

MMK: The description of your University of Chicago Fundamentals of Playwriting class is delightful. I so wish I had the time/money to participate!

[Editor’s Note: The description of Mickle’s Fundamentals of Playwrighting class reads, in part, “This workshop will explore the underlying mechanics that have made plays tick for the last 2,500-odd years, from Euripides to Shakespeare to Büchner to Caryl Churchill, Suzan-Lori Parks, and Annie Baker, etc. Students will be asked to shamelessly steal those playwrights’ tricks and techniques (if they’re found useful), and employ them in the creation of their own pieces.”]

What playwrights did you “steal” from as you were learning your craft?

MM: Every one I read, the ones I liked and the ones I didn’t. It’s an automatic thing, I think, for playwrights. But maybe the biggest Open Sesame moment was reading Jarry’s UBU ROI and seeing Caryl Churchill’s CLOUD NINE within the same month, realizing “Oh, we’re in the theater age of Anything’s Possible, Everything’s Desired.”

CB: Do you often write “lecture format” plays? How does this format serve?

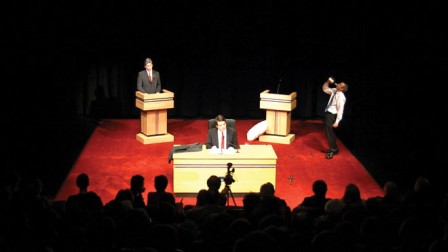

MM: Most of the plays I write are grounded in some form of performance mode that has elements of theater but is seen as Not theater. I’ve got a panel discussion play, a debate play, a play in a tele-fundraising boiler room (everyone on phones, selling), an audition play, etc. These settings might serve the audiences’ experience in a number of ways, but the main hope is that they somehow, paradoxically, ground events by wedging a kind of theater we see as “real life” theater (the lecture) into the theater we see as a place to pretend (in this case the stage of Next Act.) It’s a form of a play within a play, I suppose.

MMK: What inspired the bold choice to have Ellen and Bernard speak in verse?

MM: The verse came very late in the game, born of panic. I’d written the whole play (unrhymed) and had a good reading of it at The Goodman in Chicago. The actors were great, the direction solid, but the thing was just, you know, a half slice of American cheese. Not even bad. Just there, doing nothing. The play was due to open for my own company in six months or so, thus the panic. I went home and curled up on the bed in a quiet ball of desperation and the first couplet—the first one of the play—came to me. I remember this like it was a gift from some minor god, the one who doles out favors to obscure, quasi-experimental playwrights. I wrote (or rewrote/translated) Bernard’s first monologue that afternoon. Doing the rest took much longer, but was some of the most fun I’ve ever had in this job.

CB: As the playwright, what do you hope for an audience to gain from hearing this story in this way?

MM: An audience can sense that love, that excitement in an actor attempting something above and beyond the everyday, don’t you think? You’ve probably felt that many times on stage. Outside the story of the play or the themes, there’s just the thrill of the high-wire act of some plays. For me, it’s just a charge to see actors squeeze into the rigid suit of rhyme and then make it their own, get comfortable in it, make the predictable and artificial thing look entirely natural. It’s a great magic trick.

But, really, there’s a mystery in what exactly the pleasures of rhyme are. It’s a debate that’s been going on (to get on my pedant’s pony) for hundreds of years. People have hated it for as long as people have loved it. Today, if you’re trying to get a poem into the New Yorker, you’re probably better off not rhyming. But if you’re writing lyrics for a Broadway musical, it is practically the law that you do. (And do it perfectly, no slant or near-rhymes! Stephen Sondheim’s ghost will murder you.)

CB: Do you write poetry too?

MM: I don’t, anymore. As a freshman at U of Michigan I was very into it, as were most of those in the gang I hung out with. But they were also into theater, and the two worlds merged.

MMK: On a personal note, I am especially smitten with the story of Bernard singing to Ellen at the gig where they fell in love. I have been married to a musician for 31 years. We had met, and I was trying hard to find reasons not to be interested in him because I was exhausted by failed love affairs. He invited me to come see him play. I went, I heard, I was toast.

I am very much looking forward to starting rehearsal. Your play is just wonderful. It is smart, funny, beautiful, surprising, funny, sexy, heartbreaking and funny again. Did I say it was funny? Truly – I find that great, funny plays are rare and precious these days. I can’t wait to spend hours in a room bringing this to its feet, sharing the joy with cast and crew.

MM: I love that story of how you met your true love!

CB: Neil [Brookshire, who plays Bernard] and I have both said that part of why we love this piece so much is that it is ultimately grappling with what we feel are big, universal issues – our own mortality being at the forefront. But it’s also hilarious. And maybe, also, in a most basic sense – a love story? It’s nearly impossible to explain this play in one sentence. I have mostly just been telling people that I’ve never read anything quite like it. I would love to know how you would describe your play in a single sentence?

MM: Arg! I’m the worst person at synopsizing my own stuff. I mean, I feel like the play itself is the reduced down, pithy expression of the much larger thing that’s in my head. Just tell people it’s about sex and there’s some stage combat of a sort, do not mention the rhyming (some folks just know they hate a play in rhyme even if they’ve never heard a play in rhyme), tell them about the sex again, don’t say anything about folk music, and close with a hint about how much you get to swear.

Tickets for THERE IS A HAPPINESS THAT MORNING IS are now on sale at https://nextact.org/show/there-is-a-happiness-that-morning-is/#tickets. This production is offered live at 255 S. Water Street, Milwaukee. Performances run February 23 – March 19, 2023.

Called “One of the most original voices in American theater today” by the Houston Chronicle, with work described as “uniquely weird and enthralling” (Variety), Mickle Maher is a cofounder of Chicago’s Theater Oobleck and teaches playwriting at the University of Chicago.

Mary MacDonald Kerr has been a theater artist in the Milwaukee area for 27 years. Locally, she has directed and acted in productions at Next Act Theatre, Renaissance Theaterworks, Milwaukee Chamber Theatre, Milwaukee Rep, First Stage, In Tandem and Milwaukee Shakespeare.

Cassandra Bissell previously appeared at Next Act Theatre where she has appeared previously in THREE VIEWINGS and THE REVOLUTIONISTS. Wisconsin Credits: Milwaukee Chamber Theatre, Renaissance Theaterworks, Milwaukee Rep, Forward Theater Co., Third Avenue Playworks and 18 shows over 9 seasons at Peninsula Players. Regional (LORT) credits: Actors’ Theatre of Louisville, Arizona Theatre Co., Cleveland Play House, Court Theatre, Great Lakes Theater, Idaho Shakespeare Festival, Indiana Repertory, Northern Stage, Northlight Theatre, People’s Light and Utah Shakespeare Festival. Chicago (CAT) credits: Chicago Shakespeare Theater, First Folio, Next Theatre, Rivendell Theatre Ensemble, Shakespeare on the Green, Shakespeare Project of Chicago and Steppenwolf. Small Professional Theatre (SPT) credits: CATCO (Columbus, OH), Company of Fools (Sun Valley, ID) and freeFall Theatre (St. Petersburg, FL). She holds a BA in Gender Studies from the University of Chicago.